It’s Our River: Virginia v. Maryland, Take 1

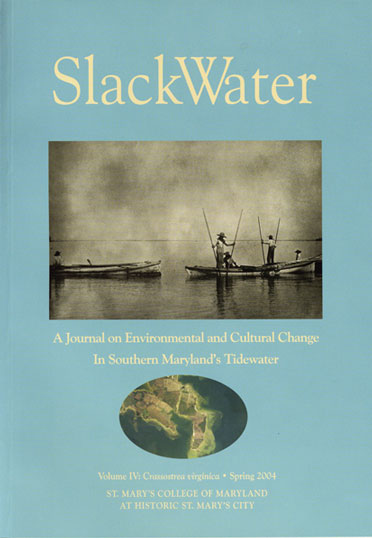

The SlackWater Center at St. Mary’s College of Maryland is a consortium of students, faculty, and community members documenting and interpreting the region’s changing landscapes. Oral histories are at the core of the center, which encourages students to explore the region through historical documents, images, literature, and scientific and environmental evidence. Some of this work has been published in the print journal SlackWater, some of which is online and some published here. The work below was first published in SlackWater Volume IV Crassostrea virginica in spring 2004.

In 1946 legislative researcher Carl Everstine estimated that roughly 62% of the commercial oyster catch from the 1944-45 season had been harvested illegally, with the majority of the illegal dredging attributed to Virginia watermen. The problem stemmed from an unwieldy governance structure in place since the 18th century. In the 1940s the Potomac was still governed by the Compact of 1785, the product of laborious negotiations between Virginia and Maryland over fishing and passage rights in the river. The Compact of 1785 effectively gave Virginia free and equal rights to the Potomac fisheries while upholding Maryland’s title to the river under the 1632 charter Charles I granted to Lord Baltimore. More significantly, it declared that any river-related legislation must be passed by both states.

In 1957, Maryland Delegate J. Frank Raley pushed Maryland to abrogate the Compact altogether, a move which prompted Virginia to take the matter to the U.S. Supreme Court. The result was the Potomac River Compact of 1958, which grew out of a bi-state commission to develop a new agreement between Maryland and Virginia.

Virginia had little trouble passing the new Potomac River Compact, but ratification was a much more difficult process for Marylanders, some of whom accused Raley of ”giving the river away.” One of the most vocal against the new Potomac River Compact was Walter Dorsey (1928-2009), state’s attorney for St. Mary’s County from 1954 to 1958 and a state senator from 1959 to 1962. Believing that the 1958 Compact put “too much power in the hands of too few,” Dorsey forced the matter to a referendum and lost. The 1958 Compact passed state-wide, with St. Mary’s County voting overwhelmingly against it, 4,245 to 1,147.

– Victoria Jones

By Bo Knutson as told by Walter Dorsey

Captain Chester Cullison was in charge of the Tidewater Fisheries Department, which is now the Department of Natural Resources, had local people working with him — a fellow named Wood from down at Ridge and the Pratt boys. But Captain Chester was pretty tough, and when I was State’s attorney, the watermen used to come to me and say, “Walter, we can’t make a living with Captain Chester, you gotta get rid of him, you gotta do something.” But there was nothing I could do about it. He was the captain, he’s gonna do what he wants. So finally Captain Chester retired, and that’s when they started bringing the Eastern Shore men in to take his place. And he hadn’t been gone a month before the watermen came and said, “Walter, what can we do to get Captain Chester back? We can’t live with these damn Eastern Shore men.” (Laughs)

You talk about Oyster Wars and my recollection is there weren’t any Oyster Wars. They were a figment of the news media trying to justify the Potomac River Compact, trying to say, “Oh you got all these terrible Oyster Wars down in St. Mary’s and Charles County.” There may have been some isolated shots fired by police officers, but whatever shooting was done was probably when the watermen were trying to elude the police. A lot of dredge boats from Virginia came out of Colonial Beach and anchored here. They dredged oysters and they wouldn’t stop, and the police may have fired at them, but I don’t think it was much of them firing back. The Virginians would come in packs, and when they saw the police, they’d all run!

Copies of this Slackwater Volume IV are available here.

I lived right over in the Seventh District in ‘57, ‘58, and ‘59 — right on the Potomac River, on Colton’s Point, across from Blackistone Island. There was no Oyster War going on, believe me. I wasn’t out there on the front lines, but I would have known about it because I used to hear all the watermen’s complaints. That’s where the watermen lived, based in the Seventh District, and they were down at my house all the time complaining. They weren’t complaining about being shot at by police officers or being shot at by dredgers from Colonial Beach. Instead, they were complaining about the dredgers themselves and asked why Oyster Police Captain Chester Cullison didn’t catch them.

As far as enforcing the laws, it was up to Maryland to enforce them; I never remember that there was much enforcement by the State of Virginia. They may have had some police boats, but I never saw one from Virginia. The dredgers would usually stay in the tributaries, so they would be prosecuted in the Virginia courts if caught. We prosecuted some Virginians here in these courts, but that was only when they were actually caught and we could prove that they had a dredge on the boat. If they were prosecuted in Virginia, they were given a slap on the wrist.

I’m sure the Maryland oystermen felt that the police had plenty of support because they were usually on the job. They were quick to spot violators. But maybe there was an isolated case where a fellow was shot; maybe he was fleeing and eluding a police officer. That sort of thing was not widespread. My thought was that whenever any shots were fired — which was rare — that they were just warning shots to stop dredgers from absconding and fleeing the police officers.

Virginia dredgers could see a police boat two or three miles away, and they’d take off and go into the Virginia tributaries. The oyster police couldn’t go in to the Virginia tributaries. They had no jurisdiction. So they might have fired a shot to scare them . . .

Anyway, the Compact wasn’t conserving anything because it didn’t regulate the fish in the whole Chesapeake Bay area. We needed to have a sincere, concentrated effort to conserve the fisheries of the Chesapeake Bay. How can you promote conservation of just the Bay? How can you promote conservation just by isolating one area to regulate when you don’t have regulation of the entire Chesapeake Bay? I thought that if we had to have a Compact, then it should include the entire area that would be affected. If it’s in the interest of conservation, then let’s approach it from that viewpoint. So, in an effort to block the 1958 Compact, I tried to get the whole Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries [included].

I knew Virginia would never go along with it. They were in favor of dredging, and of course, we were all opposed to dredging here because it would deplete the resources. In Virginia there were really no oyster rangers because most of their tributaries were leased bottoms. And they have big oyster packers who own hundreds and thousands of acres of bottom land that they’d plant oysters on. There are no public bars like we have here in Maryland. I really felt that the Compact was just a political move and that it was the Virginia packers behind it so they could lease [more] oyster grounds. We were concerned that, if this Compact were enacted, it was just a subterfuge on the part of Virginia to try to lease thousands of acres out in the Potomac River to these big commercial watermen in Virginia. That’s what we thought. In the Compact, I thought we were giving away the rights of our watermen in this County. Eastern Shore men didn’t come over here into the tributaries at that time. Watermen from St. Mary’s County and Charles County were the only ones who were actually using the Potomac River.

In the next installment, Mr. Dorsey talks about the legislative battle in Annapolis over the Compact. “I think the Compact is probably one of the worst things that’s ever happened to Maryland,” he said at the time.