SlackWater: When Electricity Came to St. Mary’s

The SlackWater Center at St. Mary’s College of Maryland is a consortium of students, faculty, and community members documenting and interpreting the region’s changing landscapes. Oral histories are at the core of the center, which encourages students to explore the region through historical documents, images, literature, and scientific and environmental evidence. Some of this work has been published in the print journal SlackWater, some of which is online and some published here. The work below was first published in SlackWater Volume V The Rural Issue in spring 2006.

Change Begins at Home

Rural Electrification and the Household Economy

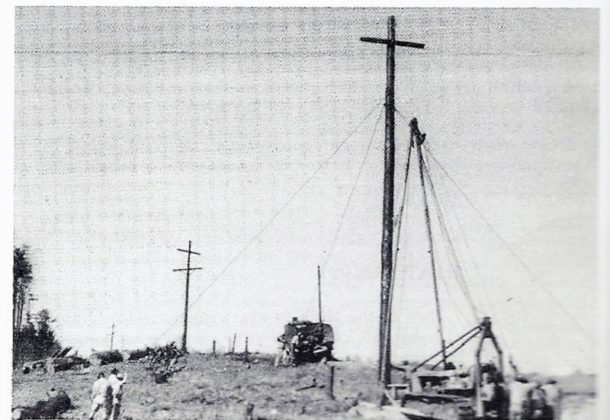

Although the first commercial power plant in the nation opened in New York City in 1882, electricity did not come to Southern Maryland for another half century. In 1936, Congress, hoping to raise the standard of living in rural communities, established the Rural Electrification Administration for the purpose of bringing electricity to rural areas. By 1938, a power plant was up and running at Pope’s Creek, Maryland, serving Charles, Prince George’s, and St. Mary’s counties. This plant was owned by the Southern Maryland Tri-County Cooperative Association, which in 1942 became the Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative, or SMECO.

Electricity – and especially electrical appliances – dramatically changed the way people lived, and nowhere was the impact more evident than in the lives of the women who ran the rural households of Southern Maryland. The vacuum cleaner, refrigerator, stove, washing machine, and even the electric food mixer revolutionized household work. Without a washing machine, for example, it could take four hours to wash a standard load of laundry; with a machine, clothes washing was reduced to just 40 minutes.

Household work was critical to the success of the Southern Maryland farm, providing subsistence and domestic support for the family. This work was provided almost wholly by women and their daughters. Women could also be called upon to assist in the fields, especially with time-sensitive chores like cutting tobacco, but their primary responsibility was to keep the household running. In the narrative fragments that follow, we hear about the nature of household work from the women who did it in rural, pre-electrified Southern Maryland.

We also catch glimpses of how electricity and the expansion of telephone service would profoundly reshape life in Southern Maryland. News that previously took weeks to reach isolated rural areas was now delivered almost overnight through the radio.

We also catch glimpses of how electricity and the expansion of telephone service would profoundly reshape life in Southern Maryland. News that previously took weeks to reach isolated rural areas was now delivered almost overnight through the radio.

Life without electricity was a fact of rural life until relatively recently. Electricity lengthened the workday and revolutionized domestic labor. With more time available, girls were able to remain in school longer and adult women could augment their family’s income, taking in outside work or working outside the home. Electricity also accelerated the process by which Southern Marylanders (and rural people everywhere) were brought into the national and global communities. The bombing of Pearl Harbor revealed the power of the radio, many powered by electricity, to galvanize a national community comprised of listeners. Locally, the telephone brought rural families into closer everyday contact.

We had a woodstove [and] we had oil lamps. No electricity. We didn’t have running water or that kind of thing; we had to pump the water and bring it into the house. Water buckets with dippers, that kind of thing.

Mildred Fletcher

Down at Point Lookout, [our] cook stove [used] kerosene and it had the oven on one side and flat burners here and you had little jar of kerosene sitting on the side that fueled the flame. You had to constantly fill up that little jar with kerosene in order to be able to cook. We didn’t have a refrigerator or anything. We had to use ice for our refrigeration.

Eunice Knott

In the wintertime, Momma would sit there by the wood stove. [She] was a wonderful woman. She’d get up in the morning by sun-up [and] cook breakfast. It was all done on a wood stove. We’d have what you call hash browns, bacon, and sausage. What you raised was what you had.

Mary Ora Norris

[For meat], my father killed at least five hogs every year. There was no ice, no iceboxes, so we had to salt the meat to keep it.

Ruth Goddard Knott

[I] used to help with the butter churning and that kind of thing. The first churn I used was a big stone jar with a stick in the center. You worked [the stick] up and down [by hand] ‘til the butter came.

Mildred Fletcher

We had to go to the next door neighbor’s house to get our water. We had to carry our water.

Helen Louise Fenwick

She [had] an electric radio. Where I lived, we didn’t have a generator. We had a battery radio. We took the battery out of our car, and sit it in the corner and hook it up to the radio and that’s what we listened to. That was the good old days.

Julius Knott, son of Ruth Goddard Knott

[When my brother died from drowning], they had his funeral at the lighthouse at Mr. Willis’ home. I was the only one from the family that went to the funeral. Momma had died, and Pop couldn’t go. See, then there wasn’t phones. There just wasn’t ways to let people know like there is now.

Mrytle Dare

Copies of this Slackwater Volume V are available here.

[Our telephone was] the wind-up kind. You had to rrrrrrrr [motions]. The Coast Guard [had the same kind] and it was a party line. You had umpteen people on the one line and if you lifted the receiver and listened, you could hear all kinds of conversations (chuckles). And we listened in on a lot of people’s conversations. So you know all what went on in the neighborhood!

Eunice Knott

There was no television back then. [But] we had an old, old roll-top radio in the living room, and I was fooling around with that. And I came across this news that Japan had declared war on the United States.

Eunice Knott

I remember vividly listening to a report of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, on a radio that wasn’t very clear, on a Sunday afternoon. Yes, I remember that vividly. It sounded like a fearful catastrophe had hit us, and people were shocked at how suddenly it hit.

J. Frank Raley