Fixing Broken Networks

By Jay Friess

Editor

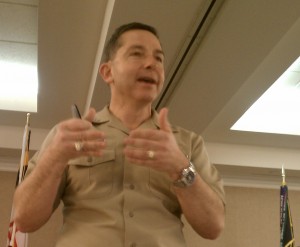

Speaking before a gathering of military officers, government program managers and contract engineers in Solomons, Maryland Tuesday, Rear Adm. David Dunaway, commander of the Navy’s Operational Test and Evaluation Force, declared that airborne data networking is broken.

“We’re broken,” Dunaway said. “And we’re especially broken in areas of interoperability.”

Dunaway made his remarks at an Airborne Networking Symposium hosted by the Southern Maryland Chapter of the Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association, which continues today.

The problem of getting aircraft, drones, ships and ground forces to all communicate seamlessly during operations is not a matter of technical prowess, Dunaway stated. It’s a matter of political will.

“It’s not that we can’t do it,” Dunaway said. “It’s that we’re not doing it. …This is really an organizational will problem and a cultural problem; it’s not a technical problem.”

This is increasingly becoming a issue as the Navy is looking to expand its array of remotely and autonomously piloted aircraft to handle everything from Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) to weapons delivery. Even pilots now have to go through a much more complex series of information gathering, data analysis and decision making before loosing a weapon at a suspected enemy.

“We’ve built in dependency on command and control and ISR in a way we never have before,” Dunaway said.

Dunaway suggested that, to begin to change this problem, program offices need to think outside their own “tribe.” He suggested that every aircraft and weapon development program needs an engineer responsible for determining if the system being developed can interact seamlessly with the system of systems that the Navy employs.

Rear Adm. William Shannon echoed Dunaway’s assessment in his observations about the programs he oversees as the executive of the Navy’s Unmanned Systems and Strike Weapons program office.

“We are largely in stovepiped communications,” Shannon said, noting that the Navy’s unmanned aircraft can communicate to controllers, but not to the Navy’s larger data systems. “Every sensor is not networked. … We are not there yet, but we are getting better. … Long term, we’ve got to get better with our [communication] standards.”

Shannon noted that Northrop Grumman manufactures the vehicles for the Navy’s major unmanned systems programs – Fire Scout, BAMS-D and UCAS-D. However, the vehicles do not share a common control station or software control environment.

“They follow no standard convention,” Shannon said of unmanned control software, noting that the interfaces bear no resemblance to either common personal computer interfaces or even video games. They also tend to try to recreate a cockpit environment, Shannon said, adding that they are being designed by manned aircraft engineers for use in testing by manned aircraft pilots. “Why do we want to create a cockpit on the ground? We’ve got to break that paradigm.”

Shannon envisions unified control system that would treat each unmanned vehicle like an asset to aid in the operators’ “god’s eye view” of the battlefield.

However, Dunaway called the concept of a unified Navy network a “pipe dream, way down the road, future text,” stating, “You got a lot of building to do to get to that point.”

And cost is always a factor. Speaking as a member of a panel moderated by Art Fritzson, Senior Vice President of Booz Allen Hamilton, Capt. Robert Dishman, former head of the Navy’s Broad Area Maritime Surveillance Demonstrator project, said that capabilities often must be traded off to budget shortfalls.

Dishman noted that the BAMS-D cannot function as a weapons targeting platform, as it was initially intended. The capability could be added in the future under later budgets.

“These types of trades happen all the time in program management,” Dishman said.