SlackWater: Navy Brings ‘Boomtown Years’

The SlackWater Center at St. Mary’s College of Maryland is a consortium of students, faculty, and community members documenting and interpreting the region’s changing landscapes. Oral histories are at the core of the center, which encourages students to explore the region through historical documents, images, literature, and scientific and environmental evidence. Some of this work has been published in the print journal SlackWater, some of which is online and some published here. The work below was first published in spring 1999 in SlackWater Volume II: Cedar Point 1942.

“This Happened Here” Part 3

World War II ended meager times for many Americans hit hard by the Depression of the 1930s, and during the war the federal government became increasingly instrumental in shaping national identity.

SlackWater attempts to suggest how Southern Maryland, in particular St. Mary’s County, was transformed from an isolated agricultural community to a newly shaped culture, one that reflected the social and economic changes of a larger nation. It uses people’s recollections as bits and pieces of history, which in a textbook sometimes lack flavor or emotion, to tell a story of what the war and all it brought meant for Southern Marylanders. SlackWater emphasizes the changes that occurred on the American homefront during the war, and how those historical occurrences have led to a thriving community.

Many newcomers today do not know Cedar Point. Those of us who now call Southern Maryland home know of Patuxent River Naval Air Station, and Lexington Park, and Town Creek. Forgotten are places like Pearson, and Fordtown, and Jarboesville. Patuxent River Naval Air Station now suggests flight simulators, weapons testing, and test pilot training, and no longer fertile farmland; the patchwork of farms and settlements has been pushed down and smoothed over to make the Navy’s mission possible.

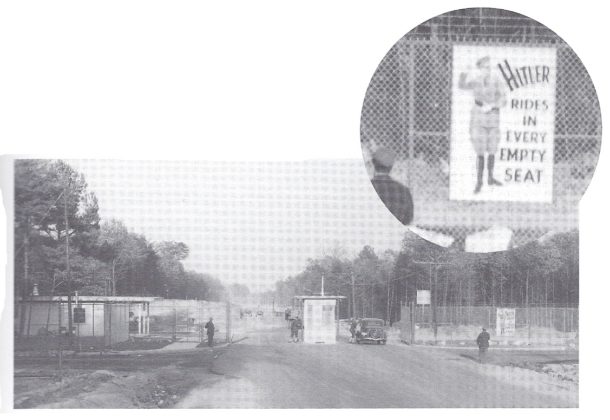

Temporary workmen’s barracks 1943. Photo Courtesy NAS Patuxent River. (Published in SlackWater: Volume II: Cedar Point 1942/Spring 1999 edition)

By all accounts these were the “boomtown” years, when workers from all over poured into St. Mary’s County by the thousands. New arrivals found themselves working 12-, 16-, and 20-hour days and having no place to sleep afterwards. Barracks on base were perpetually filled. Stories are told of exhausted workers waiting for a bunk to open up so that they could jump in for some precious rest. Natives rented out rooms to try to assuage the problem, but they could only do so much. Workers, sleeping out in the elements, invaded people’s yards and fields, even their chicken coops.

Those drawn by the short-term, high-pay opportunity came from a range of backgrounds and circumstances. In November of 1942 there were some 3,500 to 4,000 laborers living in barracks on base. That December, all civilian employees were fingerprinted and issued picture badges. These background checks indicated that “confidence men, draft dodgers, felons, liquor smugglers, prostitutes, robbers, and gamblers” were employed by the base. From March 1943 until January 1944 the Civilian Police Force made 2,204 arrests.

The boomtown years brought new stresses as well as prosperity. The numerous beer gardens and bars that lined the streets accessing the base were often rough places. The worker sleeping in yards or temporary barracks mixed uneasily with the decorated officer and the farmer whose backyard had just been turned into a runway. Tensions arose between “natives” and “outsiders.” Territorial lines were drawn. In the bars and taverns, brawls were commonplace on a hot Friday night. George Grymes stayed in most nights, slept in his “colored” barracks with his money wrapped up under his pillow. In his words: “After I’d taken the examination on the base, I went to get something to eat, and I went to a place and they was gambling. They had guns on the table, and it was just like I was in the Wild West.”

The boomtown years brought new stresses as well as prosperity. The numerous beer gardens and bars that lined the streets accessing the base were often rough places. The worker sleeping in yards or temporary barracks mixed uneasily with the decorated officer and the farmer whose backyard had just been turned into a runway. Tensions arose between “natives” and “outsiders.” Territorial lines were drawn. In the bars and taverns, brawls were commonplace on a hot Friday night. George Grymes stayed in most nights, slept in his “colored” barracks with his money wrapped up under his pillow. In his words: “After I’d taken the examination on the base, I went to get something to eat, and I went to a place and they was gambling. They had guns on the table, and it was just like I was in the Wild West.”

Slot machines were legalized and widespread. Bars and restaurants teemed with tables and machines. Even Frank Aud’s general store and post office had a slot machine. Eventually, it would take a coalition of public representatives to lobby to get rids of the slots. And, as some locals see it, the turning point in the argument would be a strong push on the part of county churches, whose Saturday night bingo games nevertheless remained.

In the earlier years the population of newcomers was predominantly male; female dancers and prostitution accompanied the changing demographics. Their later decline cannot be pinpointed as sharply as that of the gambling. … In the mid-1940s and 1950s there were stories of doctors, politicians, farmers and laborers all fraternizing in the local brothel. …

Gradually a new community arose out of this mix of laborers, enlisted men, officers, and native countians. Many of the major investors in those post-war years were big names in the county. In 1945, Jack Daugherty, for example, from Morehead, Kentucky, saw opportunity in the fledging town of Lexington Park. Funded by gamblers, he developed an array of businesses from a newspaper office to a radio station to a sporting goods center to a new bank. Other investors had roots in the county. Larry Millison’s father Hiram had run the general story on Cedar Point that survived through bartering and loaning goods to trusted neighbors. His son’s interview tells of a ledger book containing records of debts owed by fellow Cedar Point farmers, and how Hiram destroyed that book when he found out his customers had just lost their land. In 1942, Hiram purchased acreage outside the base’s main gate, a move that proved lucky, as it became the center of the newly emerging town.

No one’s life would be the same. Philip J. Bean began as a local farmer and country doctor, known for accepting chickens or a sack of grain in payment for his services. By 1942, civilians, workers, and native countians created long lines at his home that kept him tending to patients from dawn until late at night.

Next: The transformation at Cedar Point in the early 1940s mimicked national trends. Industrialization was sweeping across American farmlands. Small farmers were replaced by the industrial advances of agribusiness and machines. An era of radical national change was brought to St. Mary’s County largely through the infusion of people and funds associated with the naval base.

The first installment of “This Happened Here” [“SlackWater: World War II Transforms So. Md.”] can be read here.

The second installment [“SlackWater: Cedar Point Erased to Make Way for Base”] can be read here.

I’m alive today because my Dad, Grandfather and 2 uncles came from NW Pennsylvania to work on building the base. With no place to stay, as described in this article, my Greenwell uncle took them all to my grandparents farm in Hollywood to board. Mother was from a family of 15 Greenwell children 9 of which were girls. At the breakfast table the first day my Stanton Grandfather poked my Dad in the ribs and said “look how many girls this woman has!” Dad said, “yep, and I’m going to marry that one right there” pointing to my mother. Well yes,they were married and Dr. Bean delivered me. They had 65 wonderful years and together and I’ve always been thankful for Pax River NAS!