Steamboats Key to Local SoMD Oyster Industry

St. Mary’s County Historical Society has published Chronicles of St. Mary’s since 1953, an unrivaled trove of diligent local historians’ work, eclectic in subject and style. The Historical Society presents excerpts from a few as an invitation to explore more of our history, the shared and the unknown. A digitized record of the Chronicles is available through the member’s portal on the website and on-site research is available to all.

By Robert Hurry of the St. Mary’s County Historical Society; excerpt from Chronicles of St. Mary’s, Winter 2019

These excerpts have been edited by the publisher

The Chesapeake Bay region became the nation’s center for harvesting, processing, packing, and shipping oysters during the 19th century. Baltimore, with its harbor facilities and access to rail transportation, came to dominate the oyster market to satisfy America’s appetite for the popular bivalve. After the Civil War, smaller oyster packers began to spring up in tidewater areas that were closer to the oyster grounds. This was especially true in waterfront towns on the Eastern Shore of Maryland that had railroad access. In St. Mary’s County, oyster packers got a later start.

Lacking direct access to railroad service, southern Maryland oyster packers and shippers were centered near steamboat wharves and landings that connected its waterfront communities to nearby population and transportation centers. Never as numerous or productive as the large oyster packing establishments of Baltimore, Annapolis, Crisfield, or Cambridge, early shucking houses in St. Mary’s were concentrated in the southern part of the county and began as branches of larger packing companies.

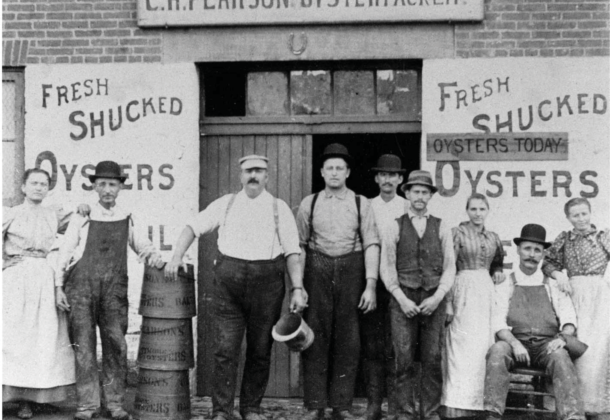

Both shelled oysters that could be opened by the consumer and shucked oysters found ready markets in restaurants, oyster saloons, and household kitchens. Fresh shucked oysters commanded a higher price in the retail market and were preferred over canned oysters by consumers. The raw oyster trade in southern Maryland catered to the metropolitan areas of the mid-Atlantic and northeast. The raw trade required cold weather or ice to preserve the product during shipping, but did not necessitate the technical expertise and capital investment needed to establish a steam-powered cannery.

Late 19th century newspaper accounts refer to the perishable, fresh-packed product as barreled oysters. After the oysters were shucked, the meats were placed in a perforated pan called a skimmer where they were drained. The oysters were then put in a large colander and rinsed with clean water to remove any dirt or grit. Once clean, the product was ready for packing. In the 1887, R.H. Edmonds described two methods, one using metal cans and the other using specially made wooden barrels, which were practiced for packing raw shucked oysters for shipment:

Raw oysters, after being opened, are packed in small air-tight cans holding about a quart, and these are arranged in rows in a long wooden box, with a block of ice between each row, or they are emptied into a keg, half-barrel, or barrel made for this purpose. When the latter plan is pursued, the keg or barrel is filled to about five-sixths of its capacity, and then a large piece of ice is thrown in, after which the top is fastened on as closely as possible, and it is at once shipped … Packed in this way, with moderately cold weather, the oysters keep very well for a week to ten days.

The earliest references to commercial oyster packing operations in St. Mary’s County were reported in the St. Mary’s Beacon newspaper in the early 1880s. The packers engaged in the raw trade and opened their shucking houses close to steamboat wharves where barreled oysters could be shipped to nearby population centers. After reaching Baltimore, Norfolk, Alexandria, or Washington, D.C., the barreled oysters were either repacked to be sold and consumed locally or transported by railroad or ship to more distant markets.

Oyster packing room of the Baltimore firm of C. H. Pearson shows the process of preparing barreled oysters for shipping. (Courtesy, National Archives and Records Branch)

The Baltimore Sun newspaper reported on the size and extent of the barreled oyster business in and around Baltimore in 1879:

Barreled oysters are selling at $2 to $5. The packers are shipping great quantities of shucked oysters every day to the interior. The consumption of oysters has grown to be something marvelous in its proportions. One of the oyster express trains from Baltimore for the West and North has for weeks left in two sections, with about 30 carloads, 16,000 to 20,000 pounds of shucked oysters to each car, aggregating, say 400,000 pounds of oysters sent away by this train every day.

The practice of shipping shucked oysters in barrels continued into the 20th century. In 1902, Jerry Wrightson employed a group of oyster shuckers at his place on St. Jerome’s Creek and shipped his product to Baltimore. In 1903, the St. Mary’s Beacon reported: “Barreled oysters are being shipped north of the Mason and Dixon’s line” and stated, “There are twenty-seven shuckers at Miller’s wharf and thousands of gallons of oysters are shipped to Baltimore every week per Weems’ Line.”

Steamboats remained an important and economical means of shipping shucked oysters to market during the early 20th century. But, as land transportation routes became more reliable and ice manufacturing more common during the 20th century, trucks were increasingly relied upon to transport raw oysters to market. After World War I, the practice of packing the shucked product directly into smaller consumer tin cans became common. These advances allowed oyster packers to sell their fresh product directly to retailers and consumers.

Local entrepreneurs capitalized on 20th century improvements in transportation and technology to spread the raw oyster packing trade throughout St. Mary’s County. No longer solely dependent on waterborne shipping, by 1920 there were 13 licensed oyster packers scattered across the county. In addition to the established packers in the southern section of the county, oyster houses operated at Abell, Avenue, Blackistone, Compton, Hollywood, Leonardtown, Mechanicsville, Pearson, and River Springs.

The whole story is available in The Chronicles available through St. Mary’s County Historical Society, which curates a repository of a unique collection of Maryland memorabilia and museum pieces displayed on the first floor of Tudor Hall and in the Old Jail Museum at 41625 Courthouse Drive in historic Leonardtown. The 18th-century Tudor Hall also serves as headquarters of the society and houses the Historical Society’s Research Center.

While much of the property and programming remains shuttered during the COVID-19 pandemic, much of the materials available through the Historical Society are digitized and accessible. To learn more visit their website linked above.

To find more posts by the St. Mary’s Historical Society, visit this Leader member page.